The following is a guest post by Stefan Troost, he describes the work he did in his bachelor thesis:

In this project we have used the RPython infrastructure to generate an RPython

JIT for a

less-typical use-case: string pattern matching. The work in this project is

based on Parsing Expression Grammars and

LPeg, an implementation of PEGs

designed to be used in Lua. In this post I will showcase some of the work that

went into this project, explain PEGs in general and LPeg in particular, and

show some benchmarking results.

Parsing Expression Grammars

Parsing Expression Grammas (PEGs) are a type of formal grammar similar to

context-free grammars, with the main difference being that they are unambiguous.

This is achieved by redefining the ambiguous choice operator of CFGs (usually

noted as |) as an ordered choice operator. In practice this means that if a

rule in a PEG presents a choice, a PEG parser should prioritize the leftmost

choice. Practical uses include parsing and pattern-searching. In comparison to

regular expressions PEGs stand out as being able to be parsed in linear time,

being strictly more powerful than REs, as well as being arguably more readable.

LPeg

LPeg is an implementation of PEGs written in C to be used in the Lua

programming language. A crucial detail of this implementation is that it parses

high level function calls, translating them to bytecode, and interpreting that

bytecode. Therefore, we are able to improve that implementation by replacing

LPegs C-interpreter with an RPython JIT. I use a modified version of LPeg to

parse PEGs and pass the generated Intermediate Representation, the LPeg

bytecode, to my VM.

The LPeg Library

The LPeg Interpreter executes bytecodes created by parsing a string of commands

using the LPeg library. Our JIT supports a subset of the LPeg library, with

some of the more advanced or obscure features being left out. Note that this

subset is still powerful enough to do things like parse JSON.

| Operator |

Description |

| lpeg.P(string) |

Matches string literally |

| lpeg.P(n) |

Matches exactly n characters |

| lpeg.P(-n) |

Matches at most n characters |

| lpeg.S(string) |

Matches any character in string (Set) |

| lpeg.R(“xy”) |

Matches any character between x and y (Range) |

| pattern^n |

Matches at least n repetitions of pattern |

| pattern^-n |

Matches at most n repetitions of pattern |

| pattern1 * pattern2 |

Matches pattern1 followed by pattern2 |

| pattern1 + pattern2 |

Matches pattern1 or pattern2 (ordered choice) |

| pattern1 - pattern2 |

Matches pattern1 if pattern2 does not match |

| -pattern |

Equivalent to ("" - pattern) |

As a simple example, the pattern lpeg.P"ab"+lpeg.P"cd" would match either the

string ab or the string cd.

To extract semantic information from a pattern, captures are needed. These are

the following operations supported for capture creation.

| Operation |

What it produces |

| lpeg.C(pattern) |

the match for patten plus all captures made by pattern |

| lpeg.Cp() |

the current position (matches the empty string) |

(tables taken from the LPeg documentation)

These patterns are translated into bytecode by LPeg, at which point we are able

to pass them into our own VM.

The VM

The state of the VM at any point is defined by the following variables:

PC: program counter indicating the current instructionfail: an indicator that some match failed and the VM must backtrackindex: counter indicating the current character of the input stringstackentries: stack of return addresses and choice pointscaptures: stack of capture objects

The execution of bytecode manipulates the values of these variables in order to

produce some output. How that works and what that output looks like will be

explained now.

The Bytecode

For simplicity’s sake I will not go over every individual bytecode, but instead

choose some that exemplify the core concepts of the bytecode set.

generic character matching bytecodes

-

any: Checks if there’s any characters left in the inputstring. If it succeeds

it advances the index and PC by 1, if not the bytecode fails.

-

char c: Checks if there is another bytecode in the input and if that

character is equal to c. Otherwise the bytecode fails.

-

set c1-c2: Checks if there is another bytecode in the input and if that

character is between (including) c1 and c2. Otherwise the bytecode fails.

These bytecodes are the easiest to understand with very little impact on the

VM. What it means for a bytecode to fail will be explained when

we get to control flow bytecodes.

To get back to the example, the first half of the pattern lpeg.P"ab" could be

compiled to the following bytecodes:

char a

char b

control flow bytecodes

-

jmp n: Sets PC to n, effectively jumping to the n’th bytecode. Has no defined

failure case.

-

testchar c n: This is a lookahead bytecode. If the current character is equal

to c it advances the PC but not the index. Otherwise it jumps to n.

-

call n: Puts a return address (the current PC + 1) on the stackentries stack

and sets the PC to n. Has no defined failure case.

-

ret: Opposite of call. Removes the top value of the stackentries stack (if

the string of bytecodes is valid this will always be a return address) and

sets the PC to the removed value. Has no defined failure case.

-

choice n: Puts a choice point on the stackentries stack. Has no defined

failure case.

-

commit n: Removes the top value of the stackentries stack (if the string of

bytecodes is valid this will always be a choice point) and jumps to n. Has no

defined failure case.

Using testchar we can implement the full pattern lpeg.P"ab"+lpeg.P"cd" with

bytecode as follows:

testchar a -> L1

any

char b

end

any

L1: char c

char d

end

The any bytecode is needed because testchar does not consume a character

from the input.

Failure Handling, Backtracking and Choice Points

A choice point consist of the VM’s current index and capturestack as well as a

PC. This is not the VM’s PC at the time of creating the

choicepoint, but rather the PC where we should continue trying to find

matches when a failure occurs later.

Now that we have talked about choice points, we can talk about how the VM

behaves in the fail state. If the VM is in the fail state, it removed entries

from the stackentries stack until it finds a choice point. Then it backtracks

by restoring the VM to the state defined by the choice point. If no choice

point is found this way, no match was found in the string and the VM halts.

Using choice points we could implement the example lpeg.P"ab" + lpeg.P"cd" in

bytecodes in a different way (LPEG uses the simpler way shown above, but for

more complex patterns it can’t use the lookahead solution using testchar):

choice L1

char a

char b

commit

end

L1: char c

char d

end

Captures

Some patterns require the VM to produce more output than just “the pattern

matched” or “the pattern did not match”. Imagine searching a document for an

IPv4 address and all your program responded was “I found one”. In order to

recieve additional information about our inputstring, captures are used.

The capture object

In my VM, two types of capture objects are supported, one of them being the

position capture. It consists of a single index referencing the point in the

inputstring where the object was created.

The other type of capture object is called simplecapture. It consists of an

index and a size value, which are used to reference a substring of the

inputstring. In addition, simplecaptures have a variable status indicating they

are either open or full. If a simplecapture object is open, that means that its

size is not yet determined, since the pattern we are capturing is of variable

length.

Capture objects are created using the following bytecodes:

-

Fullcapture Position: Pushes a positioncapture object with the current index

value to the capture stack.

-

Fullcapture Simple n: Pushes a simplecapture object with current index value

and size=n to the capture stack.

-

Opencapture Simple: Pushes an open simplecapture object with current index

value and undetermined size to the capture stack.

-

closecapture: Sets the top element of the capturestack to full and sets its

size value using the difference between the current index and the index of

the capture object.

The RPython Implementation

These, and many more bytecodes were implemented in an RPython-interpreter.

By adding jit hints, we were able to generate an efficient JIT.

We will now take a closer look at some implementations of bytecodes.

...

elif instruction.name == "any":

if index >= len(inputstring):

fail = True

else:

pc += 1

index += 1

...

The code for the any-bytecode is relatively straight-forward. It either

advances the pc and index or sets the VM into the fail state,

depending on whether the end of the inputstring has been reached or not.

...

if instruction.name == "char":

if index >= len(inputstring):

fail = True

elif instruction.character == inputstring[index]:

pc += 1

index += 1

else:

fail = True

...

The char-bytecode also looks as one would expect. If the VM’s string index is

out of range or the character comparison fails, the VM is put into the

fail state, otherwise the pc and index are advanced by 1. As you can see, the

character we’re comparing the current inputstring to is stored in the

instruction object (note that this code-example has been simplified for

clarity, since the actual implementation includes a jit-optimization that

allows the VM to execute multiple successive char-bytecodes at once).

...

elif instruction.name == "jmp":

pc = instruction.goto

...

The jmp-bytecode comes with a goto value which is a pc that we want

execution to continue at.

...

elif instruction.name == "choice":

pc += 1

choice_points = choice_points.push_choice_point(

instruction.goto, index, captures)

...

As we can see here, the choice-bytecode puts a choice point onto the stack that

may be backtracked to if the VM is in the fail-state. This choice point

consists of a pc to jump to which is determined by the bytecode.

But it also includes the current index and captures values at the time the choice

point was created. An ongoing topic of jit optimization is which data structure

is best suited to store choice points and return addresses. Besides naive

implementations of stacks and single-linked lists, more case-specific

structures are also being tested for performance.

Benchmarking Result

In order to find out how much it helps to JIT LPeg patterns we ran a small

number of benchmarks. We used an otherwise idle Intel Core i5-2430M CPU with

3072 KiB of cache and 8 GiB of RAM, running with 2.40GHz. The machine was

running Ubuntu 14.04 LTS, Lua 5.2.3 and we used GNU grep 2.16 as a point of

comparison for one of the benchmarks. The benchmarks were run 100 times in

a new process each. We measured the full runtime of the called process,

including starting the process.

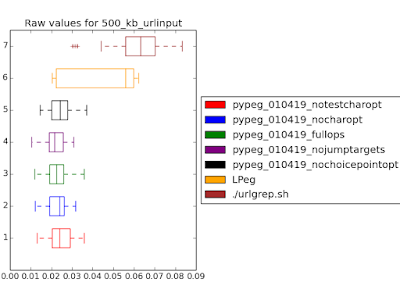

Now we will take a look at some plots generated by measuring the runtime of

different iterations of my JIT compared to lua and using bootstrapping to

generate a sampling distribution of mean values. The plots contain a few different

variants of pypeg, only the one called "fullops" is important for this blog post, however.

This is the plot for a search pattern that searches a text file for valid URLs.

As we can see, if the input file is as small as 100 kb, the benefits of JIT

optimizations do not outweigh the time required to generate the

machine code. As a result, all of our attempts perform significantly slower

than LPeg.

This is the plot for the same search pattern on a larger input file. As we can

see, for input files as small as 500 kb our VM already outperforms LPeg’s. An

ongoing goal of continued development is to get this lower boundary as small as

possible.

The benefits of a JIT compared to an Interpreter become more and more relevant

for larger input files. Searching a file as large as 5 MB makes this fairly

obvious and is exactly the behavior we expect.

This time we are looking at a different more complicated pattern, one that parses JSON used on a

50 kb input file. As expected, LPeg outperforms us, however, something

unexpected happens as we increase the filesize.

Since LPeg has a defined maximum depth of 400 for the choicepoints and

returnaddresses Stack, LPeg by default refuses to parse files as small as

100kb. This raises the question if LPeg was intended to be used for parsing.

Until a way to increase LPeg’s maximum stack depth is found, no comparisons to

LPeg can be performed at this scale. This has been a low priority in the past

but may be addressed in the future.

To conclude, we see that at sufficiently high filesizes, our JIT outperforms

the native LPeg-interpreter. This lower boundary is currently as low as 100kb

in filesize.

Conclusion

Writing a JIT for PEG’s has proven itself to be a challenge worth pursuing, as

the expected benefits of a JIT compared to an Interpreter have been achieved.

Future goals include getting LPeg to be able to use parsing patterns on larger

files, further increasing the performance of our JIT and comparing it to other

well-known programs serving a similar purpose, like grep.

The prototype implementation that I described in this post can be found

on Github

(it's a bit of a hack in some places, though).